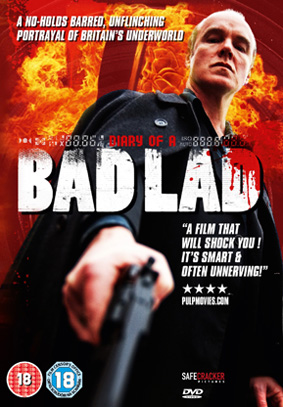

Producer Jonathan Williams says he didn't have time for conflicts whilst making the upcoming 'Diary of a Bad Lad.' He also explains why the project was so long in production. A frank exchange with WIDESHOT's James Macgregor.

Jon Williams, Underground Filmmaker

Film: Diary Of A Bad Lad

Blackburn, North West

by James MacGregor

The film is about what happened to documentary filmmaker Barry Lick and his crew as they attempted to make Diary of a Bad Lad, 'a video-diary about some really nasty criminals'. Unexpectedly and very quickly they get in over their heads inside the sleazy world of drug smuggling, hard-core pornography, loan sharking, corpse disposal, murder & much more...

Diary Of A Bad Lad, (Fiction Documentary Feature, 2004, DV/ DX110,DVX100,DSR200,PD150)

What is your background as a writer and producer?

I'm 55 years old and all my working life I have been some way involved with fringe theatre, acting, television documentary production and teaching media.

What gave you the idea for Diary of a Bad Lad?

I had quite a number of filmmaking anecdotes that I used to tell to my students, some of them were personal experiences some were things I had heard about from other people. I was looking for some way in which I might use them. Then along came Lock Stock and that spate of UK gangster films, all of which I was disappointed by because I didn't think the characters in these films were believeable. It was as if they all walked around wearing sandwich boards saying "I am a gangster - arrest me!" - but no-one ever got arrested. I wasn't interested in the people who don't get caught. I was interested in people like a cocaine importer operating out of Manchester who was caught, but who was investing his money in a chain of mobile phone shops. He was only arrested because someone in Columbia mentioned his name in a telephone conversation that was being tapped by the American Drugs Enforcement Agency. That was his bad luck, as it were. If his name had not been picked up he might have been written about in some Manchester business magazine as a successful entrepreneur.

At the same time, I thought of a character, Barry Lick, who was mad enough to see if he could make a documentary about someone involved in large-scale drug importation - a business man who didn't get caught . That character I also invented and called him Ray Topham, who had become a very successful property developer. Lick gets the chance to make his personal documentary after being suspended from college because of his unorthodox views; he told his film students they would probably be far more successful in the film business making porn movies. He's had the idea of the film for ages, now he has the opportunity to make it.

Why did you first write Diary of a Bad Lad as a novel?

It soon became apparent to me that it had to be worked out in precise detail and I wrote it out as a series of diaries, diaries that the crew kept whilst they worked on this insane project. This was to do a dry run on paper of the whole process, to work out precisely how we could do it and at the same time to produce a treatment we could write a script from.

How did people receive the story?

It was 80,000 words, but everybody who read it could not put it down.

They all read it at one sitting.

You don't find believable hard men in most British gangster movies - how did you make sure yours were?

We got a couple of local bouncers. These guys were amazing, absolutely amazing! Big Billy Hodge goes in for World's Strongest Man competitions, six foot six tall and he weighs about 25 stone and he has got a beer belly, but he runs quite a few doors in this area and we had another one of his bouncers who just always looks seriously deranged.

They were brilliant because they were playing a couple of characters similar to themselves. They could put their real selves into these situations and with no ego about it at all. You couldn't have better people to direct. Everything was so thoroughly understated by them. This is not some actor going to play a hard man. You have a couple of really nice guys who also just happen to be really hard men and they were playing themselves in these fictitious situations.

How did your collaboration with director Michael Booth and camera operator Paul Gordon come about?

Michael has done quite a few shorts, Paul works with Michael and Paul normally does corporate stuff as a jobbing cameraman and editor. We are very much into the B movie/ entertainment/horror left field. We had had quite a few things turned down by various funding bodies. We always fell between two stools with some funding people saying "This is too commercial - you should be pursuing this commercially" and then the commercial people would say "This is too extreme, too experimental." We knew that with this project, if we were to go ahead, we were on our own.

What resources did you have available to shoot the film?

We started off with a little 3-chip Panasonic camera and a Bayer gun mike. We knew that the crew for the film was also going to be part of the cast, so we already had a core cast-and- crew. We knew if we started off with the crew's quest to track down this shady character filming as they go, we would have footage we could show people what we had done with just a small crew and on the back of this, bring other resources in.

The shoot took three years, why so long?

We always knew it would take a very long time, since we were planning to make it on as close to no money as possible. Also, if we had planned a three- week shoot, we would have chosen to do something completely different, set in one location. If you were making this as a documentary, you would have no idea how long it would take you to make it either.

How did you manage to schedule and hold your cast and crew over that period?

It was semi shot-in-order although a fair bit was out-of-sequence. We knew that shooting on no money, the film would have to take second place to what everybody else did. At the same time, the basis of the offer to everyone we approached was a profit-share. People had other reasons to come on board as well. One of our cast teaches drama at the University of Salford, so he normally can accept only small acting parts. For him, this was an opportunity to play a really substantial role. Another factor that helped us was that we rapidly moved to shooting with two cameras, one camera observing the documentary crew "in action", so this meant we could do scenes in real time using two cameras. There might be three or four extended takes, all done in real time, so we had plenty of choice for the edit.

What camera and format did you choose?

Our kit grew pretty rapidly from the little Panasonic 3-chip.

We switched to the Sony PD 150 and another Sony camera that looks like a Betamax in miniature - can't remember the exact name. We deliberately shot everything with very long takes because we shot documentary style and we wanted to edit it documentary style.

What size of crew and cast?

Two people on camera and one holding the microphone and the person with the microphone was usually playing in front of the lens. And of course the cameras get in each other's shots.

The cast absolutely loved it because they could act out whole scenes rather than do things in fragramentary fashion. We did not even need to go back and do cutaways because with two cameras running, we already had them!

With a 3-year schedule how did you manage continuity?

I had one slight personal advantage in front of the cameras. My mother is hairdresser and I was responsible for my own haircut! The film days-out-of-days are meant to be over an extended period, so people's appearances do change over time. We were aware of the need for continuity and covered it most of the time. Where we didn't, you can't really see the joins.

We had problems with a big night club scene, shot with the club empty one Sunday, where their expensive computer-controlled lighting rig was meant to be available to us but we couldn't get it to work. We got enough lights working to generate an atmosphere, so we only shot the scenes set in a VIP area, for which we used the balcony bar. Later we went back and shot the full nightclub scenes about five nights later, so it's not a continuity problem. We did have seasonal continuity problems though. The film is set in spring, summer and autumn, with a very large number of locations, so continuiity meant we had to match things up with seasonal vegetation, though we could shoot a few interiors in winter. We shot for as long as we could the first year, but then we just had to wait out the winter and go again the following April.

What sort of locations were you using and where were they?

We used three different night clubs and a lot of different houses. We were very fortunate with a local business man John Sturgess, who runs a plastic extrusion factory in Darwen - he ended up playing a hit man for us - and he has a large converted farmhouse which we used as the property developer's house, so we shot a lot of stuff in that. It was all located largely in Blackburn, a bit in Darwen, some in the Ribble Valley and some in Bolton - oh yes and Leeds/Bradford International Airport.

Wasn't Manchester Airport closer - it was on the right side of the Pennines for you?

Manchester wasn't easy to deal with. I think they get large number of requests to film.

There's lots of form-filling, lots of bureaucracy and they charge you lots of money.

But Leeds/Bradford Airport is after publicity! They were extremely nice and verty friendly, as long as we didn't want to shoot in their busy peak May to October. We shot there at the end of last April when it was about 27 degrees and it looked like June.

What were the high spots for you?

All of it really. It was like a roller coaster once it was under way. It was always going to get to the end. One thing that really pleased me was that over such a long period, nobody wanted to drop out from us. They were committed, as if this was the most important thing they have ever done and it may continue to be so for some considerable time.

You are also cast as the lead - any writer/producer/perfomer conflicts there?

When not performing, I was mapping out the future, looking at the schedule, calling people, checking on their availability, checking back with other possibilities. Then there was clearing locations use for certain dates, making sure everyone knew how to get to the locations, making sure there was going to be food there, so everyone could be fed. Conflicts? I had no time for any conflicts!

Moving to the edit - what shooting ratio did you finally have?

Round about twenty to one, forty hours of film, edited to one hour fortyfive minutes.

It has been cut in two people's bedrooms. Michael, who directed it, is a complete obsessive and will happily work until four thirty in the morning. He did the roughcut down to about two hours which he did on his own. Then he had a hard drive disintegrate on him, so we had thirty hours of footage to digitise and start again. This time, we did a very quick rough cut and showed it to Liverpool director Chris Bernard who shot Letter To Brezhniev. Chris is a bit like Lily Savage on speed, but with a sharper tongue! He did a mixture of tearing the roughcut to pieces and telling us it was absolutely brilliant. He spent six hours looking at it with us. He liked the material, he liked the whole idea. It was like a theatre director giving notes. He didn't sit down and watch it start to finish he sat down and hit the pause button and said "This has gone on far too long, get rid of him!" "You don't need that!" Things like that. It was a masterclass really, enormously useful to us and something that we really needed, becauseafter three years and a hard disc crash, you have been with that material for a very long period of time. We approved of everything he told us to do with the roughcut. We needed someone to come in at that point and be very brutal and forthright so that we could argue better among ourselves as the edit moved forward. He said things like "That scene's in the wrong place" and maybe one of us already felt that and one of us didn't, but we were now able to address that and agree with Chris and find a better place for it. We had a lot of reflective discussions coming back to look again on the points he had picked up on.

So overall, what was Chris Bernard's final verdict on Diary of a Bad Lad?

Chris looked at it in an edit suite next door to the Liverpool Everyman Theatre and afterwards we went to the theatre bar and some of his ex-Brookside actor colleagues were in there and asked him what he'd been up to recently. He said "Oh hello, I've just been next door looking at their film - Oh God, it's brilliant! - It has got loads of gorgeous men in it who get their kit off!"

That actually reflected back to something that had been said about it a long time before. We had actually showed some work in progress to one or two people and Danny Moran from the Manchester magazine City Life saw it and he said he was surprised at how, working no budget, we had persuaded people to go totally nude. One of the sequences Chris really loved involved a young couple who were heavily in debt to the property developer, who's also a bit of a loan shark, but not a stereotyped Lock Stock type of loan shark. He suggests they could make a bit of money and clear some of their arrears by making an amateur porn film. They say they can't, because they haven't got any equipment, but he suggests these documentary people might lend them some. The film crew go along to record an enforcement meeting with this couple in debt -because the heavies want to show that they are not thugs- and find their equipment is to be used to make an amateur porn movie. Now even amateur porn movies requre a knowledge of the filming conventions and things that apply in porn movies like any other genre and this couple have absolutely no idea about that, so this is the worst amateur porn movie ever. From a pornographic point of view it is a total disaster because they film themselves failing to make any porn. Chris Bernard really liked that sequence, he thought it was hilarious.

Is bizarre black humour one of the film's strengths?

The film is full of black humour. I mean, what do you do as a film crew if you are in a room interviewing someone and someone else in the room dies?

What do you do?

In this case they died of a drugs overdose, so the death does not have to be connected with this room, so you can bundle them into the boot of a car and go and dump the body somewhere else. There are a lot of bizarre situations like that in Diary of a Bad Lad, interesting takes on the human condition.

What useful techniques did you discover during the filming of Bad Lad?

I can recommend editing via email! We did a lot of our edit discussions by email. Rather than discussions face-to-face as it were, you individually look at it, think about it and then commit those thought to email and send them off and then a lot of email discussion ensues. This means you really think things out much, much, better AND it keeps everyone working together nicely. You get greater clarity and fewer problems of ego loss!

Where do you place this film in the market?

What we always wanted to end up with was something like "Man Bites Dog."

That was a film that appeared at the time there was a spate of serial killer movies, a project started by some Belgian film school students about 1989-1990 using some old black and white 16mm stock. They imagined this surreal world in which every neighbourhood had its serial killer and everybody knew who they were. You know, in the corner shop the guy says "Packet of Golden Virginia please," and gets asked "Blown anybody interesting away recently, then?" They shot it as a documentary on the neighbourhood serial killer and it has a lot of absolutely horrendous killings in it and at first it is screamingly funny, but the guy is playing up to the camera and it is becoming more extreme as it goes along, so it starts to become more of a conspiracy between him and the filmmakers, so to speak. They cease being passive observers and effectively become active participants and it is no longer possible to laugh at it.

It was made on an absolute shoe-string. There are a few classic ultra-low budget films, like El Mariachi made for $10,000. It is a wonderful piece of work but it looks as though it was made for $10,000. You look at the Blair Witch Project and you ask how on earth did they manage to spend that amount of money, because it looks like a crap student production you would give a bad mark to. You look at Man Bites Dog and you would not think it had been made on a shoe- string, you go, "This is a bloody good film!" This is because the way that they shot it was exactly right for the subject matter. It's not like El Mariachi which was made as a calling card and you then go and remake it properly and call it Desperado. Man Bites Dog is an absolutely superbly crafted film in its own right. We wanted to make something that would make people say it was good; not that it was good because it was made for £3,500. We just wanted people to say this is a good film. We shot it documentary style with this DV kit because that is what was needed. But, because you are shooting documentary style but you are actually shooting a piece of fiction, you know exactly what is going to happen, so you end up with something in which the pictures look better than in documentary, because they are planned.

Would you describe it as a spoof documentary like Spinal Tap or Best in Show?

Things like Spinal Tap and on TV like Paul Calf's Video Diaries are all done tongue-in-cheek. This is more like The Office, it is played out seriously. It doesn't have any bad in-jokes.

For our type of film, the bar was set by Man Bites Dog, a wonderful film. We believe that with Diary of a Bad Lad -and this is no disrespect to a very good film- we have kicked that bar up several notches.

So what do you see as the market for this film?

The people that Withnail and I appeals to. These are would-be documentary filmmakers, they are out of their depth. They do things which they shouldn't do. It should appeal to the student audience, to the Friday night six-pack-and-a-video-from-the-local-shop audience who like to take out something that is most definitely a left field underground movie. But all of that is at the bottom end. DVD is an enormous market. But it has opened up distribution avenues for many underground/low-budget movies which haven't had, and often weren't aimed at, cinema exhibition. In many ways you could say it's caused a renaissance for the B-movie. One example of this is Alex Chandon's very low budget horror feature, "Cradle of Fear" which almost as soon as it was finished they started marketing on DVD via their website with copies being shipped through a Dutch company. And they claim that from these direct sales they went into profit before the film had even got a BBFC certificate. Ok, now Cradle of Fear did have one thing going for it as it starred the Goth-bad, Cradle of Filth's lead singer, Danny Filth - but hands up all those who've heard of either Danny or his band? There's a huge direct-to-DVD market and we have had discussions already with Elite Entertainment, Image Entertainment and Unearthed Films, who all specialise in underground cult movies. But we didn't just make something cheap. We wanted to make something cheap and beautiful, within our resources. It has taken a while, but we think we have made it beautiful.

What about cinema distribution?

I would definitely like to see this in the cinema. Next year the Film Council's 150 digital screen project should be complete, Easter 2005. Those screens are going to be short of product and it is when things first start that they are most open. Then they get taken over by the vested interests and settle down and become predictable. We want to get in there before they become predictable. In the US, Landmark Theatres, America's biggest arthouse chain, is already running digital projection in about 175 screens. This is a heck of a lot more screens to go after than a handful of arthouse theatres, and there are more coming on stream all the time. What's more, with anything new, the field is pretty much wide open - until the big boys move in and take it all over - so it's up to all DV-filmmakers to get involved in shaping the future for digital exhibition. We are not against transfering DV to film, not in the least, provided that the maths add up. Top quality transfer costs around £50,000 or more, and after that there's the print costs. Now if you look at the chart in the Guerilla Film Makers Blueprint detailing the UK box office gross for all UK films released in 2001, most of them would not have netted enough to recoup the transfer costs.

Obviously if someone came along offering a major deal for Bad Lad on film we'd bite their hand off, but I wouldn't be crying in my soup if they didn't.